We first met Abimelech in one of the “wife-sister” episodes. (Follow the link, you can scroll down to the subheading Abimelech King of Gerar: Another Unwitting John?) After sending Hagar and Ishmael away, Abraham encounters him again (Genesis 21:22-34).

At that time Abimelech, with Phicol the commander of his army, said to Abraham, “God is with you in all that you do; now therefore swear to me here by God that you will not deal falsely with me or with my offspring or with my posterity, but as I have dealt loyally with you, you will deal with me and with the land where you have resided as an alien.”

And Abraham said, “I swear it.”

(Gen 21:22-24 NRS)

Abimelech was king of Gerar at that time. Why is he so keen to make Abraham an ally, even though he resides there as an alien? He had taken Sarah into his palace, because Abraham told him she was his sister (didn’t mention she was his wife). God appeared to him and told him the only reason God did not kill him was he did not know Sarah was his wife. God told Abimelech to return Sarah to her husband and ask him to pray for God to forgive him. That was how he concluded God is with you in all that you do.

Since God is with Abraham, and he almost lost his life because Abraham had dealt falsely with him, he wants to be sure Abraham understands I have dealt loyally with you, so you will deal [loyally] with me. When he first came there, Abraham thought people in this area had no fear of God. Clearly, they do now. Either he wants to remind Abraham he dealt loyally with him, or he wants to be sure Abraham understands, “You know how you told me Sarah was your sister but didn’t tell me she was your wife? Don’t ever do that again. You may have thought we don’t fear God, but you know better now.”

Yes, Abimelech, and by the Way…

When Abraham complained to Abimelech about a well of water that Abimelech’s servants had seized, Abimelech said, “I do not know who has done this; you did not tell me, and I have not heard of it until today.”

(Gen 21:25-26 NRS)

When Abraham complained to Abimelech… A better translation would be, But Abraham complained to Abimelech… (NAS), or Abraham, however, reproached Abimelech (NAB; see Translation Notes). Abimelech says he didn’t know about it. He also says, you did not tell me. Why? I understand why he wants to be sure Abraham knows he did not order that or even know about it. It was the same defense he gave to God. “I did not know. He did not tell me.” It was true then. I guess we have to assume it is true now as well.

Certain Details Left out

So Abraham took sheep and oxen and gave them to Abimelech, and the two men made a covenant.

Abraham set apart seven ewe lambs of the flock. And Abimelech said to Abraham, “What is the meaning of these seven ewe lambs that you have set apart?”

He said, “These seven ewe lambs you shall accept from my hand, in order that you may be a witness for me that I dug this well.”

Therefore that place was called Beer-sheba; because there both of them swore an oath.

(Gen 21:27-31 NRS)

It is not clear at first that they are making covenant. Or maybe for them, it was clear when Abimelech asked him to swear to me here by God. I’m not sure how this particular covenant ceremony works. Abraham took sheep and oxen and gave them to Abimelech. Did they cut them in half and each walk between in turn, swearing the terms of the covenant (Gen 15:9-21)? If so, why did Abraham set apart seven ewe lambs of the flock? Maybe they slaughtered them for the covenant.

But then why did he say, “These seven ewe lambs you shall accept from my hand,” as if they were a gift? Did he give them or slaughter them? Which animals were slaughtered and how? That was normally how a covenant would be sealed. Was the agreement sealed with the gift of oxen and sheep, or the gift of the seven ewe lambs?

This is one of the difficulties in reading not just the Bible but any text from a culture that is markedly different from ours. I bet the original audience was so familiar with this type of covenant that the author did not need to explain those details to them. So unless archeologists find some more specific accounts of similar ceremonies, those details are lost to us.

They Invoked the Seven

But however they ratified the covenant, setting apart seven ewe lambs was important to this origin story of how Beer-sheba got its name. In Hebrew, be’er = “well,” and sheba` = 1) seven; 2) oath. The oath was sealed by setting apart seven ewe lambs. This is one of those moments that makes the Hebrew text much more intriguing than the translation. The fact that sheba` is the root of both “take an oath” and the number seven indicates there was probably an ancient connection between seven and giving an oath. One of my professors said in the ancient Canaanite (or other local) pantheon, there was a team of seven gods associated with oaths, sort of like in Greek mythology, there were three fates and three furies, who were for the most part inseparable. To “invoke the seven” meant to make an oath.

First it says Abraham gave Abimelech sheep and oxen in order to secure his claim to the well. Then Abraham says, “These seven ewe lambs you shall accept from my hand, in order that you may be a witness for me that I dug this well.” That’s what makes the details of the ceremony confusing. What did he give to Abimelech? Were any of the animals slaughtered for the ceremony?

Once again, I think I may be confused because the original audience did not need these details explained to them.

From Oral to Written

Maybe there were two accounts of this story, one where Abraham gave an unspecified number of sheep and oxen, and one where he gave seven ewe lambs. The author did not want to choose one and leave out the other, so he put them both in, i.e., looks like another doublet.

The terms of the covenant are 1) they will each deal truthfully and loyally with each other, and 2) Abimelech recognizes this well belongs to Abraham. And once again, they are at peace.

Therefore that place was called Beer-sheba. Abraham and Abimelech get credit for naming the place. Later, as with the wife-sister episode, we have almost the exact same story between Isaac and Abimelech (Gen 26:26-33). Isaac is given credit there for naming the place Beer-sheba, and it is also based on an oath between him and Abimelech of Gerar. Even the name of the commander of his army, Phicol, is the same in the Isaac account. Pharaoh was the title not the name for the king of Egypt. Abimelech could similarly be a title not a name. But could Phicol be the title of the commander of the army? I doubt it.

So the wife-sister episode was not the only case where we have the same story, same characters, but switch Isaac for Abraham. It is extremely unlikely this exact same story happened to both Abraham and Isaac. Again, this looks like a doublet. I attribute this to the fact that these stories circulated orally for a long time, probably hundreds of years, before they were written down. In that time, Abraham could change to Isaac in some localities. Any other differences in those stories could be attributed to the same thing.

Anachronisms

When they had made a covenant at Beer-sheba, Abimelech, with Phicol the commander of his army, left and returned to the land of the Philistines.

Abraham planted a tamarisk tree in Beer-sheba, and called there on the name of the LORD, the Everlasting God. And Abraham resided as an alien many days in the land of the Philistines.

(Gen 21:32-34 NRS)

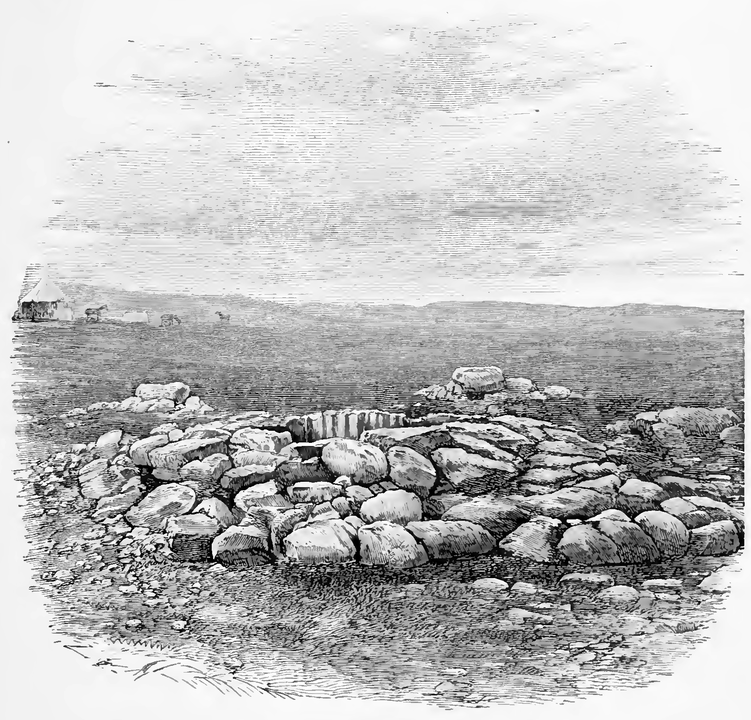

Beer-sheba was an important location in the Negev Desert. It marked the southern extent of the land of Canaan. The biblical site is believed to have been at Tel Be’er-sheva, which is a few kilometers east of the modern city. Archeological excavations indicate it became a major city in the tenth century BC, with streets laid out in a grid and separate areas for administrative, commercial, military, and residential use. This again is centuries after Abraham. Archeologists found evidence for settlements as early as the fourth millennium BC, but there appears to be a gap in settlement from about 3200-1100 BC.

It appears to be the earliest planned city in the region. “From Dan to Beersheba” became a common expression for the entire cultivated land of Israel. Several wells were dug there, many of them attributed to Abraham and Isaac.

The river on the map is called the Nahal Beersheva. It is actually a wadi, so it is dry during the summer months. However, the wells plus a cistern to collect water during the wet months ensure water supplies year round. Its water sources made it a target for conquest, and it was destroyed and rebuilt many times.

The Land of the Philistines

The Philistines did not appear in the land until hundreds of years later. They are not listed among the nations Abraham’s descendants will displace in Gen 15:18-21, and from lists of nations Moses says the Israelites would conquer (Deu 7:1 and 20:17). In the time of the Judges, they were among the deadliest of Israel’s enemies. They are associated with “the sea peoples” in Egyptian texts.

The most commonly held belief is they came from Crete in the twelfth century BC. They settled mostly along the Mediterranean coast in the area today called the Gaza Strip. The most famous Philistines from the Bible are Delilah and Goliath.

This type of anachronism might give us a clue to when the stories were first written down, at a time when the Philistines were active in the area. Another possibility the Rabbis propose is that “the Philistines” Abraham encountered were actually a different people than the ones who dominated the Israelites during the time of the Judges.

Abraham Planted a Tree…

A tamarisk tree most likely refers to the Tamarix aphylla species, typically found in northern Africa and western Asia. It grows needles instead of leaves (the meaning of aphylla) and can grow to a height of fifty feet. It is also called an athel tree, athel pine, or salt cedar (because it excretes salt on the needles, making them sometimes appear white). The shade provided coolness and increased the moisture in the air underneath. As the dew collected on the needles in the morning, they could provide a source of salt. As the moisture evaporated during the day, it would cool the shade even more.

Most other times when Abraham called on the name of the LORD, he built an altar. This is the only place where the Bible says Abraham planted a tree. It think it is significant that this takes place after Isaac was born. Planting a tree is something you do not just for yourself but for future generations. Now that he has secured his claim to this well, the tree will provide shade not only for himself but for Isaac, his children, and grandchildren.

…and Called on the Name of the LORD

Abraham…called there on the name of the LORD, the Everlasting God. There is obviously a special meaning to this. Beersheba later became a major cultic center of Israel.

The LORD spoke to Hagar, Isaac, and Jacob there. When Abraham called on the name of the LORD, it was probably under that tree. Calling on the name of the LORD, along with creating physical landmarks to worship the LORD (altars or a tree), may have referred to his actions to make the LORD known to his neighbors. We also have this from the NET translation notes,

Heb “he called there in the name of the LORD.” The expression refers to worshiping the LORD through prayer and sacrifice (see Gen 4:26; Gen 12:8; Gen 13:4; Gen 26:25). See G. J. Wenham, Genesis (WBC), 1:116, 281.

NET, tn 64.

The Everlasting God

In Hebrew, this is ‘el olam (See Translation Notes). Olam does not always mean “eternal” or “everlasting,” but as an attribute of God, I think it is appropriate to translate it that way. A comma separates “the everlasting God” from the LORD. That indicates he uses this phrase to describe the God he has come to know as Yahweh, “the LORD.” I wonder, though, if this could be a name for God, the LORD God Everlasting.

Olam can also be spatial, meaning “the world,” or “the universe.” On that note, I will close with this from Matthew Henry.

In calling on the Lord, we must eye him as the everlasting God, the God of the world, so some. Though God had made himself known to Abraham as his God in particular, and in covenant with him, yet he forgets not to give glory to him as the Lord of all: The everlasting God, who was, before all worlds, and will be, when time and days shall be no more. See Isa. xl. 28.

Commentary on Genesis 21:33.

PSA: Easiest Way to Plant a Tree (or Several) Like Abraham

The earth has become so politicized that too many Christians treat caring for the land, air, and water as completely opposite from worshiping God. How did that happen? Abraham planted a tree AND called on the name of the LORD, probably from under that same tree. Why not? Didn’t God create trees and call them good (Gen 1:12)? You do believe God created heaven and earth and everything in it (plants, animals, land, water, and humans), don’t you?

We’ve cut down a lot of trees in the last century, but here’s an easy way to help replace some of them. The Arbor Day Foundation has a new campaign. For each dollar you donate, they will plant a tree. Their goal is to raise $20 million to plant 20 million new trees. Go to teamtrees.org or #teamtrees, and like Abraham, for just a few dollars you won’t even miss, you can leave something that will benefit the earth, your children, grandchildren, and generations to come.

Translation Notes

וְהוֹכִ֥חַ אַבְרָהָ֖ם (Gen 21:25 WTT) But Abraham complained…. The vav at the beginning is translated “When” in the NRSV and ESV. That makes it sound like this could have taken place at a later time. But, however, or then makes it clearer that Abraham said this following Abimelech’s request.

The verb yakach is a hiphil perfect 3rd person masculine singular. It means to complain, reprove, or reproach.

Hol3332 יכח

hif.: pf. –1. set s.one right, reprove: a) abs. Jb 3212; b) w. acc. Is 113; w. l® Is 114; c) w. ±al (+ person) reproach s.one for s.thg Jb 195, w. °el go to law with Jb 133; w. b® requite s.thg 2K 194.

Halladay

The LORD. When the “Lord” appears in all capital letters, it refers to “the divine name,” YHWH, pronounced Yahweh. Most Jews do not speak or write the divine name out of reverence. They will often use the Hebrew word for “Lord” (Adonai) or “the Name” (Ha-shem) instead.

The everlasting God, Heb ‘el `olam. אֵ֥ל עוֹלָֽם׃ (Gen 21:33 WTT).

El is the most common word for “God” in the Hebrew Bible. Olam, translated here “everlasting.” As an attribute of God or part of God’s name, it could refer to either God’s eternal nature or the scope of God’s sovereignty as “the world” or “the universe.”

References

Carolyn Roth, “Abraham Planted Tamarisk Trees,” God as a Gardener (blog), Carolyn Roth Ministries, March 24, 2011, https://godasagardener.com/2011/03/24/abraham-the-tamarisk/

Gill, N.S. “Understanding the Philistines: An Overview and Definition.” Learn Religions, Apr. 17, 2019, https://learnreligions.com/the-philistines-117390

Tel Beer Sheva National Park (brochure).

“Who Was Delilah in the Bible?” Got Questions. Accessed October 31, 2019, https://www.gotquestions.org/Delilah-in-the-Bible.html

Wikipedia